Link to the video on the Oxford Brooks Video Portal

One of the articles that has had the biggest effect on how I train is a survey article by Stephen Seiler. Published in 2009, I found it in 2012 and it was the first peer reviewed article that I had seen which laid out the case for polarized training, and even included some findings for recreational athletes.

I had seen research that showed that polarized training, with split of 80% low intensity (LIT) and 20% high intensity (HIT) was optimal for elite athletes who train >10 hours a week. But what about schmucks like me, who train for fun and have jobs and lives. The key question for me was whether the ratio between LIT and HIT should change if the amount of training is lower? The article directly addresses that question…

This was hugely influential for me and I took the advice to heart. I tried to keep the intensity of my endurance workouts low, and the duration as long as I had time for.

The next bit of Seiler wisdom that I found helpful was a study about individualization of training. I have previously written about it here. The great thing about this study was reinforcing just how big the differences in response was between different athletes for the same training stimulus. He cited a study that was comparing different approaches to block periodization. There was a slight, statistical advantage to one approach, but the variation of response between athletes in each training group was much larger. His conclusion was that the same approach will not work for everyone. This is a pretty important lesson to learn since there are a lot of people who will cite their own results (or a national team’s results) as “proof” that a certain approach works.

So much of what works and doesn’t work has to do with how well a training approach matches your basic physiology and current training state. If you have tons of slow twitch muscles and do better at long distances, then you are likely to have different training needs than if you a fast twitch sprinter. In my own training, it has become apparent over time that I need a LOT of low intensity rowing to make improvements in my endurance. Others can by with a lot less.

So, it is with that background that I watched the video linked at the beginning of this post. I am inclined to pay attention to stuff that he presents because it seems to be well researched, and because it has resulted in good results for me.

This video reviews a fair amount of stuff that he has done before, but introduces a couple of useful conceptual frameworks to understand training.

The first is Seiler’s Hierarchy. Here is a link to an article explaining it. This set’s up a pyramid to illustrate the priority of different elements of training on race day performance.

At the base of the pyramid is training volume. As he puts it, there is a lot of peer reviewed research that shows a strong correlation between training volume and race performance. Miles do make champions.

The next level of the pyramid is High Intensity Training. The point here is that you need more than just the long slow stuff to actually improve. In addition, you need training that is hard enough to push your heart rate to 90% of your max, or higher to deliver adaptation. So, within that framework, I guess it is safe to safe that “No Pain / No Gain”. He discusses potential ways to do High Intensity Training and cites a study comparing 4 minute, 8 minute, and 16 minute intervals. He didn’t show this in the video, but it summarizes the finding of that study.

He made the point that there might be a sweet spot around the 90% HR level and that workouts that maximized the time at or around the 90% level might be more effective than shorter workouts that achieve higher heart rates, but for shorter durations.

The third level of the Pyramid is Training intensity distribution. This is where polarization comes in. He presented findings from rowing, skiing and running that showed that elite athletes generally spend their time training at much slower or faster paces than the actual race pace. This is where 80/20 comes from.

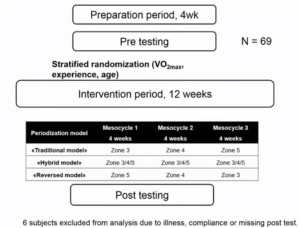

These three tiers represent the solid base of a training plan. Beyond that, you get into areas that are likely to have an impact, but the effect is less and the research is less solid. In the linked presentation, but not the video, he goes into detail about the study on block periodization studies. This research compared three block periodization strategies.

Then they looked at the results for the athletes that participated.

So, basically, all three worked great for some athletes and didn’t work at all for some athletes. This is the basis of his talk about individualization. You need to track what you’re doing and if you aren’t making progress, you should try something different with regard to periodization. There is good evidence that doing the same thing for longer than 8-10 weeks will result in diminished improvement, but it doesn’t matter as much what change you make.

The remaining levels of the pyramid are essentially the icing on the cake. They have been shown to have some benefit on race performance, but can’t be used to substitute for having a good base.

The other useful concept in the video was a discussion of dose/response curves. He described the similarity between training and medication. Basically, you have two effects as you increase the dosage of something on the subject. There is a desired effect, and there are side effects. The desired effects of training are increases in maximum power, VO2Max, Lactate Threshold, and aerobic endurance. The side effects of too much training are injury, illness and in my case an angry spouse.

Each curve is basically s-shaped. You need to get to some minimum dose before you start to see the desired effect, then that effect increases with increasing dose. At some level, the desired effect levels off, even with higher doses. The key to finding the right dose is figure out a level where the desired effect is maximized, but the side effect is still low. This is a good concept to keep in mind to ward off the “more is better” mindset. It is also useful to keep in mind around polarized training. The intent of long slow training is different than that of intense HIT. Each has it’s own dose / response curve, but they can effect each other. A way to think of this is that the desired effect curve is specific to the exercise intensity, but the side effect curve is driven by sum of all the training.

The challenge is that it’s pretty tough to know where the knees of the desired response and side effect curves are in practice. That’s where we end up relying on rules of thumb. Examples of these rules:

- You need to accumulate time above 90% HRMax to get a good response to HIT

- That the side effects of LIT volume are driven mostly by the specific type of sport being trained. They are lower for running and higher for non-impact sports like rowing

- That decreased Heart Rate Variability is a sign of over training

These are all pretty squishy and that’s where training planning gets tougher.